Three hundred million years ago a tree living insect developed wings. It was the world’s first flyer.

On our pilgrimage to visit significant places in aviation history we travelled to England and mapped a trail of air shows and air museums to see the machines flown by the men and women we’ve been living with in our minds for three years while we’ve been researching, writing and rewriting a book for children 9 + about the first Australian flyers who helped change Australia through their vision and courage. The shape of the book has also changed over the years but finally ‘The Amazing Australians in their Flying Machines’ is almost completed and is due out with Walker Books in 2017.

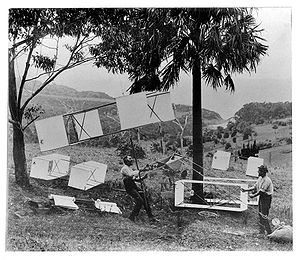

As Australians we were delighted to see a tribute to Lawrence Hargrave in the London Science Museum because with his invention of the Box Kite he is one of the founding fathers of flight.

With human flight achieved one of the first training aircraft for the Australian Flying Corps at Point Cook was named after Lawrence Hargrave’s invention the Bristol Box Kite. This replica is featured in the Shuttleworth Collection.

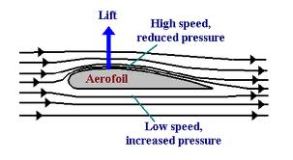

Richard Williams, the first Australian military pilot took to the air in this amazingly fragile looking arrangement of wood, cloth and wire. If there was any wind it was unsafe to fly. To test for the right flying conditions he would pull out a silk handkerchief and if it fluttered it would be too windy and he stayed on the ground.

During the First World War he was in command of 1 Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps fighting the Turks and the Germans in the Middle East. The job of 1 Squadron was mainly reconnaissance, taking photos of enemy movements. B.E.2s and the R.E. 8s built by the Royal Aircraft Factory were used. We were able to view these aeroplanes in the Graham-White Hangar at Hendon Royal Air Force Museum.

Aeroplanes were becoming more robust but the B.E. 2 and R.E. 8 were not as fast or maneuverable as the German aircraft and many pilots and observers were killed when their machines were shot down. Richard Williams demanded better planes. The squadron was finally given the new Bristol Fighters. We watched one flying at Old Warden aerodrome on a warm, blue-sky day.

Many early Australian aviators began their flying career during World War One.

Ross Smith, who flew the Bristol Fighter in 1 Squadron Australian Flying Corps, later became famous for being the first, with his crew, to fly from England to Australia.

Ross Smith with observer/gunner E.A. Mustard in a Bristol Fighter (photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial)

Hudson Fysh, also in 1 Squadron was an observer/gunner on the Bristol Fighter and he went on to be one of the founders of QANTAS airlines.

When World War One ended the Bristol Fighter was converted to a passenger plane by putting a dome over the observer/gunner’s seat.

Norman Brearley, who also flew in WW1, started Western Australian Airways, the first scheduled airline to fly in Australia, ordered six of these planes that were now called Bristol Tourers.

The Tourer carried only one pilot and one passenger although two could be squeezed aboard. One time at Western Australian Airways a second pilot had to travel and there were already two passengers in the back. Charles Kingsford Smith, another WW1 flyer who became famous, was the pilot in the front seat so the second pilot sat on the bottom wing and hung on tightly to the strut between the two wings. Everyone reached the destination safely.

At Hendon Royal Air Force Museum there was a Bristol Fighter with no fabric covering the wings and fuselage and it’s possible to see the similarity between the world’s first flyer and these early flying machines – so delicate, so easily breakable and yet they flew.

Bravo all those amazing Australians in their Flying Machines!