John Duigan – the first Australian to design, build and fly his own aircraft.

And he knew my grandfather. This was because they were both officers of the 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, stationed on the Western Front during the First World War. My grandfather, Captain Errol Knox, the recording officer for 3 Squadron notes in the official war diaries kept at the Australian War Memorial that Captain John Duigan was posted to 3 Squadron in January 1916. In David Crotty’s excellent book, on John Duigan ‘A Flying Life’ there is a group photo of 3 Squadron taken in December 1917 that shows all the officers including John Duigan and Errol Knox who are both in the front row. There’s another photo in the book that shows four men standing in front of an aeroplane. Only two are named, John Duigan and Major David Blake, the commanding officer. When I looked at the man to the right of Major Blake I thought he looked a lot like my grandfather. Scanning the photo closely I could see there were two pips on his shoulder indicating he was a captain but there were no wings on his uniform so he wasn’t a pilot. It seemed possible. I emailed the author but there hadn’t been names on the photo and he hadn’t the time to identify anyone but the two important to his research. I showed my mother the photo and she did immediately recognize her father so that’s good enough for me.

At the time my grandfather was only 26 years old so at 33 years old John Duigan was one of the older pilots and officers in 3 squadron. The main job of this squadron was reconnaissance. This meant taking photos of the enemies’ movements. For this job they flew the Re8 aircraft (the aircraft that’s behind them.) It was said to be slow and heavy and not the most popular plane of the first world war machines. It was even described by another Australian aviation hero, P.G. Taylor, as a flying field kitchen. In the right hands though it could respond and John Duigan among others fought and won a number of air battles against the more nimble German planes.

At the time my grandfather was only 26 years old so at 33 years old John Duigan was one of the older pilots and officers in 3 squadron. The main job of this squadron was reconnaissance. This meant taking photos of the enemies’ movements. For this job they flew the Re8 aircraft (the aircraft that’s behind them.) It was said to be slow and heavy and not the most popular plane of the first world war machines. It was even described by another Australian aviation hero, P.G. Taylor, as a flying field kitchen. In the right hands though it could respond and John Duigan among others fought and won a number of air battles against the more nimble German planes.

It was the 3 squadron that was involved in one of the famous events in the Great War – the death of the Baron Richthofen

The story, as written in the 3 squadron diaries, is that the Baron’s Flying Circus of about half a dozen red triplanes had been spotted by pilots of the 3 squadron on the morning of 21st April, 1918. Everyone knew that the Baron was out for a kill. He had just got his 80th victim and was after number 81 – an inexperienced young pilot from the RFC who had discovered his gun had jammed was trying to fly for home. As the pair weaved at low level above no man’s land between the two fronts the leader of the RFC spotting the problem came in behind and shot at the red triplane just before it disappeared behind the trees. Although the plane had been hit the pilot appeared to be very much alive as he was still flying after his intended victim only now he was over enemy lines. As soon as he was close enough Australian soldiers began firing and suddenly the red triplane seemed to go out of control and then it landed heavily in a nearby field. When soldiers and medical crew got to the plane the pilot was still alive.

The story, as written in the 3 squadron diaries, is that the Baron’s Flying Circus of about half a dozen red triplanes had been spotted by pilots of the 3 squadron on the morning of 21st April, 1918. Everyone knew that the Baron was out for a kill. He had just got his 80th victim and was after number 81 – an inexperienced young pilot from the RFC who had discovered his gun had jammed was trying to fly for home. As the pair weaved at low level above no man’s land between the two fronts the leader of the RFC spotting the problem came in behind and shot at the red triplane just before it disappeared behind the trees. Although the plane had been hit the pilot appeared to be very much alive as he was still flying after his intended victim only now he was over enemy lines. As soon as he was close enough Australian soldiers began firing and suddenly the red triplane seemed to go out of control and then it landed heavily in a nearby field. When soldiers and medical crew got to the plane the pilot was still alive.

‘Kaput!’ were his last words (according to Wickipedia). When they went through his pockets for papers they found out he was the pilot who called himself the Red Eagle but who has been known ever since as the Red Baron.

In an extract in the book, ‘The Battle Below’ written by Commander H.N. Wrigely, it says my grandfather, E.G. Knox was at the medical examination of Baron Richthofen’s body and agreed with Major Blake’s report that the pilot was killed by a single bullet wound that went under his armpit and out through his chest and from the angle could only have come from a bullet fired from below being fired by an Australian infantry soldier. Captain Brown, a Canadian pilot flying for the RFC has officially been given credit for death of the Red Baron but there has been a lot of controversy over this.

Because the 3 Squadron were given the task of recovering the body and the plane most of the famous plane was stripped for ‘sounvenirs’ and our family story is that my grandfather ended up with the Red Baron’s very pistol. It hung on the wall of our family home for many years and any visitor who remarked on it was told the story. One of those visitors, one day ‘souvenired’ it too so it will be interesting to know if it will come to light one day. Whether Captain John Duigan ended up with a souvenir as well I don’t know but it seems he was one of the pallbearers at the funeral of the Red Baron. I think I also spotted my grandfather saluting as the body passes by.

The drive to Mia Mia where a memorial has been erected to John Duigan’s feat of being the first Australian to design, build and fly an aircraft is down a long, narrow road. It was late afternoon and it had been raining but the clouds lifted and rays from the sun hidden behind the thick, dark clouds appeared as a shaft of light and lit up the granite monument. Three kilometers above us we could hear but not see a passenger jet heading north, the passengers probably reading the inflight magazine, watching the news on the inflight entertainment, maybe sipping on a cup of tea or something stronger, completely unaware that below was a place that had created Australian aviation history. In the distance behind the monument above a low hill a flock of white cockatoos swirled up and away at the cracking sound of a gun shot.

We saw also that this memorial had been unveiled by Air Marshall Sir Richard Williams K.B.E. C.B. D.S.O. He was next on our list of amazing Australian aviators who had achieved an Australian aviation ‘first’.

I also found a newspaper article from the Argus in 1911. I love the way these articles were written then because they give such immediacy and drama to an event of long ago so I’m posting it here. For those with short concentration spans be warned it’s around 3,000 words. It is well worth the read though to get the real feeling of the moment when John Duigan took to the air in his own home built aeroplane.

AUSTRALIAN AVIATOR.

VICTORIAN DESIGNED BIPLANE.

YOUNG ENGINEER’S ENTERPRISE

SATISFACTORY FLIGHTS.

By OLD BOY.

On the top bough of a dead giant gum- tree, growing on the bank of the Stone-Jug Creek which runs through the Spring Plains sheep property, between Mia Mia (four miles from Redesdale) and Heathcote, a yellow-crested cockatoo sat acting as sentry for his fellows quietly feeding in a crop some distance away. The time was 5 o’clock on the morning of January 25 and the sun was just rising behind the neighbouring hills. In the growing light the cattle were browsing and the scene was one of pastoral peace. A warning screech from the cockatoo was answered by the “chuckle,” “chuckle” of the flock in token that they had accepted his signal, and the cattle–their attention turned from feeding on the grass by the creek–stood up to look at something new. The Spring Plains homestead was just rousing for the work of the day when from a shed at the rear a large unwieldy looking object was drawn out, and with great care wheeled slowly down the steep hill to the creek. It was this which had caught the eye of the sentinel cockatoo, and no wonder that he screeched his warning, for his domain–that of the air was to be assailed by the first Australian aeroplane designed, built and flown by a young Australian.

The Spring Plains Estate belongs to Mr. J. C. Duigan of Ivanhoe, whose sons live on the station and manage and work it. Mr Reginald Duigan is the manager, and his elder brother, Mr. J. R. Duigan, assists him, and, as a skilled engineer and mechanician, attends to all the mechanical work on the station. Here, in his spare time, and in most adverse circumstances, he has designed and built an aeroplane, and has succeeded in flying.

Mr. John Duigan, the successful builder and aviator, was educated at Brighton Grammar School under Dr. G. H. Crowther. After a short course at the Working Men’s College, he went to England, where, entering Finsbury Technical College, London, he studied under Professor Sylvanus Thompson, and took out his diplomas in electrical and motor engineering. After a short period of practical work with the Wakefield and District Light Railway, between Wakefield and Leeds, he returned to Victoria, and saw more practical work in the service of G. Weymouth Proprietary Ltd., electrical engineers, in Melbourne. Then he went to join his brother at Spring Plains and almost immediately conceived the idea of flying.

It was about four years ago, when aviation was becoming a possibility, that Mr. Duigan began by building a pair of immense wings 15ft x 3ft., with a hole in the centre for his body. These were made in a day, and as quickly discarded, for beyond a heavy fall there was no result. The first attempt ended in smoke in more ways than one, for the wings which would not fly were used for fire-lighting. When Wilbur Wright made his first flights in France, Mr. Duigan obtained a picture of the Wright machine and built one on a smaller scale. He had no engine, but single-handed, and with the ordinary tools found in the station work shop, produced a “glider” of 20ft span, with which, after considerable difficulty, he had some useful practice, but, owing to gusty winds, was unable to rise more than 4ft at any time. This was in March1909.

Three months later the library at Spring Plains was enriched by a present from a former comrade at Finsbury College of Sir Hiram Maxim’s book on “Natural and Artificial Flight.” The thirst for knowledge of the air had been whetted by the previous attempts, but with this new book the young Victorian found himself supplied with accurate data for calculations. At first the purchase of an engine from Paris seemed beyond his means–£400 was the price quoted–and the idea of making a power-driven machine seemed as far off as ever.

The determination necessary for a pilot of the air was, however, firmly fixed in Mr. Duigan, and this difficulty was soon overcome. A Melbourne engineer (Mr J. E. Tilley) undertook to provide an engine as light and powerful as could be obtained from Europe, and at a much lower cost. It was to be a four-cylinder air-cooled 86 x 108, and to weigh about 100lb. He also secured a propeller 7ft. diameter and 6ft 6in. pitch, which, with a speed of 800 revolutions per minute, allowing a slip of 20 miles per hour, provided a speed of 30 miles per hour to the machine. Subsequently the propeller was altered, and Mr. Duigan designed and made a new one, 8ft. 6in. in diameter and 10ft. pitch, in order to give an increase of speed to about 40 miles per hour, which he considers necessary for proper flight.

Mr. Duigan prepared his own plans and drew up his own specifications, and then commenced the work of construction in a shed specially built for the purpose. He chose mountain ash for the woodwork, which, though very elastic and light, was very hard to work. The station workshop provided few facilities for the task, and from first to last Mr. Duigan toiled single-handed. He was sole designer and mechanic. He had never seen an aeroplane, but his thorough grounding in mechanics, his practical motor and engineering experience, and his indomitable patience and perseverance gradually overcame every difficulty. One trouble, and cause of much loss of time was his distance from Melbourne, and with an unsatisfactory train service, he found that whenever he required anything he could do it better by a journey over rough bush roads on his motorcycle, a journey of 80 miles each way. This journey to and fro he sometimes accomplished in a day, in order to get back as quickly as possible to his shed, in which much of the work was done by lamp or a candle light.

It is unnecessary to go into detail as to the various contrivances employed by Mr. Duigan. He was his own carpenter, turner, fitter, brazier, blacksmith, and often toolmaker as well. His little work-shop, overlooking the flat which was subsequently to be his flying ground, fairly hummed with the noise of hammer and saw and plane and the clang of his anvil, and gradually the machine assumed shape.

The weight of all the wood had to be calculated, and as it was dressed to size and shape, had to be weighed, from time to time, to see when the limit allowed was reached. The aviator in the making was working it all out for himself and as he slaved at it, giving it all the time he could spare–for the services of a skilled mechanic were largely availed of on the station–he brought in adaptations and improvements which are unknown in any other machine. Sir Hiram Maxim’s book had laid the foundation; knowledge, ingenuity, and mechanical skill had caused developments. One ingenious improvement was the institution of air springs for the running wheels. Mr. Duigan had great difficulty in getting the pistons to hold air, but the result has been full compensation for all the trouble, for air is infinitely superior to steel for springs, and much cheaper and lighter than rubber. The cups are made of rubber, lubricated with flake graphite and glycerine, and are thus free, and absolutely air-tight. The material for covering the planes was only decided upon after repeated experiments, a rubber fabric, fairly light and strong, manufactured by the Dunlop Rubber Company, proving most suitable and at the same time less expensive than anything else. The main planes were covered in position, while all the others were first covered and then fixed in their places. The engine having been placed in a firm bed, the machine was ready for use, but in the numerous trials on the ground Mr Duigan found that the drive from engine to propeller shaft, which was by 1 5/8in. rubberised leather belt, 7/8in. deep, would not prove satisfactory and eventually a steel chain was adopted.

Mr Duigan tells the story of his first trials in these words:– When everything was fixed in position, I got my brother to help while I ran the engine. We put chocks to the wheels and he held against it while I tried one cylinder. This ran all right, but shook everything terribly, so I tried two cylinders. When both got going the pro- peller began to hum, and so did the dust.The two made a pretty good wind in the shed. As everything seemed all right, I next tried the whole four, and as soon as they started there was a gale, with the machine pushing hard to get away. How- ever the engine was running badly, missing and spluttering the whole time. Ex-haust springs were rather weak, and when these were strengthened things were a bit better, but still a long way from right.

When the engine was missing, of course, it shook the machine up a lot, so that I did not like running it. The carburetter seemed too small so I took a large ‘Schebler’ out of an American motor bugegy that we have, and fixed it on. The next trial was quite different, for the engine raced away without a misfire, and very little vibration, while the push was very much greater. This was so satisfactory that after a little tuning up we took it down to our so-called flying ground. To get it there we had to take it down a hill of about 1 in 4, through two fences and across a creek. After a bit of a struggle we got it there undamaged and I climbed into the seat–or rather on to the board that served as a seat–and with some misgivings started the engine. As soon as my friends let go she ran along the ground in good style, and seemed very steady. This run ended up a fairly steep hill, and she took it easily, with the engine throttled. I had several runs up the hill to get used to the control, which was regulated thus– Right hand works the elevator; left hand works the ailerons or balancing planes, and also the switch stopping the engines; left foot works the rudder. After getting some confidence, and seeing that nothing had given away, I tried a run downhill, with the engine well throttled. This time I did not do quite so well, for first I swerved to the left, caused by the wind blowing a bit side on, and then right around to the right, doing a figure of 8. As the ground was a ploughed paddock, I thought the wheels would have gone, but they stood up all right. The machine heeled very little while turning round, the speed being about 12 miles per hour. To make things safer, I made a spring skid to go under each wing tip to check it, should it heel over much. The next trials went far better, for I first ran fast up the hill, when she nearly lifted, and as I now found I could steer straight, I had enough confidence to try fast down. This time she did a bit of a ‘hop’ when I tilted the front plane up, and steered straight and level. In the next run, the little wheel under the back, which had never been satisfactory, hit the ground sideways, and all buckled up. The spring fork arrangement on this wheel also dug into the ground, and the run finished with the little wheel scraping along sideways like a disc plough. The only damage done was to the wheel and fork, the former being buckled and the latter bent. The fork was a motor-cycle one, so it augured well for the strength of the plane that it was unaffected. To stop this happening again, I put a long ash skid in place of the wheel and fork, and this seemed to make the running gear right, for I have had many runs since, and nothing has given way except one wire stay to the propeller blades, which I replaced with stronger

wire.”

The initial difficulties having been over-come, and Mr Duigan having obtained full confidence, he tried a real flight, and on October 7, 1910, succeeded in obtaining a flight of 196 yards, the bottom of the machine being about 12ft. above the ground. Since then Mr. Duigan has been constantly experimenting and making minor alterations and improvements, and altogether has made about 15 flights, some of them over 200 yards at an altitude of about 15ft. He has instituted water cooled heads, made with copper water jackets, and has made a radiator, each tube containing 50 pieces soldered together, or 500 in all. The total cost of the raw materials in the biplane as it now stands, with the exception of the engine, is about £75, but this of course does not allow anything for time or travelling. The dimensions of the planes are–Elevating plane 2ft. 6in. x 12ft.; main planes, 24ft. 6in. by 3ft. 6in.; rear plane 3ft. by 12ft. rudder, 10 square feet; balancing planes, 20 square feet; wheels and tyres are 26in. by 2¼in. All the wires are piano wire, and all joints have steel plates top and bottom, with bolts through. All bolts are 3-16in. except the main uprights, which have ¼in. bolts, and the engine is held by 5-16in. bolts. The total weight, including a 10st. operator, is 630lb., and the area about 240 square feet.

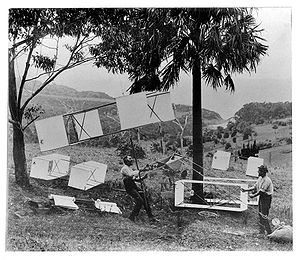

Mr. Duigan’s biplane, based on Sir Hiram Maxim’s book, resembles Farman’s biplane in some respects, and in many others is quite unique. When one sees the difficulties the surroundings, and talks to the designer and inventor, one realises what it all means to him, and has meant. The biplane as it stands to-day in its shed at Spring Plains is a monument to Mr. Duigan’s industry, and as he moves about among its intricacies of wire and plane one sees that it is alive to him. When, with the assistance of his brother and a handy man, he draws it out of its shed, and laboriously but tenderly drags it down a steep hill to the creek, over a wooden plank bridge specially made over the rough ground a distance of about half a mile, one is more than ever impressed with the difficulties.

On Wednesday morning Mr. Duigan had a special flight for the benefit of a representative of “The Argus” and “The Argus” photographer. As we looked at the flying ground–a flat beside the creek, half a mile long, by a quarter of a mile wide–we were directed by Mr. Duigan where to stand. He has a knowledge of photography and before mounting to his seat he walked to a spot 150 yards away, and, dropping his handkerchief, said “I’ll fly over this spot, so you know where to stand.” The breeze was fairly strong from the south-east, rather across the flight, and blowing in gusts, but this did not deter him. As he walked about, the cockatoo screeched his warning to his fellows again, and seemed indignant that anyone should trespass on his domain. The cattle, driven off the flat, stood on a hill near by, until some of them, unable to restrain their curiosity, ventured back again.

Mr. Duigan was lifted in to his seat, his brother stood behind him and gave the propeller one or two sharp turns, and then stepped clear of the planes. Then there was a whirr of the propeller, and we could see it flashing in the sunlight as it gained momentum. Then the chocks which had held the wheels were pulled out and the biplane bounded forward. She ran nearly 100 yards, and then, travelling at a speed of 12 or 15 miles an hour, Mr. Duigan raised the elevator, and the huge machine left the ground. This was a “hop.” She rose about 6ft., and seemed to be alighting again, when, with another push of the right hand, the elevator went up again, and the machine rose. She reached fully 20ft. from the ground, and as she passed us Mr Duigan could be seen with his machine completely under control. For 200 yards she kept on like this, flying at a speed of 25 miles an hour, when a gust of wind coming down an opening in the hills brought her round towards the creek, and Mr. Duigan lowering the elevator, she dropped to the ground, and, running lightly for a few yards, stopped. It was a highly interesting sight, but the most emphatic impression was that the machine was quite under control. The mad rush through the air was directed, controlled and regulated by the young man who had created this wonder of the air, who knew every movement of the machine and who appeared to be, not merely the driver, but the spirit, the whole being of the flight.

As the machine slowed down Mr. Duigan leaped to the ground and steadied it. The cockatoo gave one final screech and flew hurriedly away, while from their feeding ground,his fellows mounted in a cloud, and, circling round, crowded into another dead gum tree half a mile away, and down the wind came an angry chattering. One wished he could have translated that bird debate, for without doubt it was full of protest. Man had for those birds, once more trespassed! Not content with interfering with their feeding grounds, the owners of the station had entered into a domain previously sacred to the feathered tribe. As the machine was wheeled back to its shed, one speculated if accompanying the birds’ protest there was not a note of wonder and of admiration.

The flight satisfied the onlookers that Mr. Duigan was quite at home in his aeroplane, and that, given enough power –his engines are now only 20-horse power –he might accomplish anything.